Trapper has well spoken.

We in Germany have two different types of reversers.

The one with a lever, like in the old 0-4-0 locomotive "Landwuerden":

You can see the lever on the right side of the boiler back end... the throttle a ring shaped handle on the top of the boiler, difficult to see in the picture.

All other engines got screw driven reversers. We call such srews also spindles, because need to turn for operation

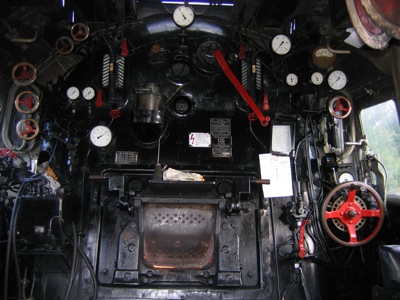

Watch the right side of the cab and note the large wheel, this is the handwheel to move the reverser. In Germany we had no browns engines or air cylinders for moving the linkage. So there is no Johnson bar anymore.

The Johnson bar is a lever with a ratchet mechanism, to keep the lever in dinstinct position on a given quadrant. On our screw linkage drivers there is no ratched anymore. You can see in the middle of the reverser wheel a disc with holes in it. A small locking mechanism uses these holes to keep the reverser wheel in the given position.

Trapper told about the effects one can feel on the reverser if the engine is moving under steam. Now we have to think about this:

A steam locomotive with a Johnson bar is shunting a huge freight train. Small locos might not have the look, but some of them could move 2000 metric tons - not fast, but slow and continuos. Let's consider a small shunting engine pulling a freight train on shunting backwards... After pulling, the train gets in motion and because of good rolling of the train the driver does not shut the throttle to adjust the engine, he want's to uphold the pulling force, but reduce the amount of steam taken by full stroke admission. So what to do? Trapper mentioned before: You have to adjust the cut off, and as more you get close to the center, as better.

So our engineer grips the Johnson bar, unlocks the ratched and...

Well, Trapper said, there is huge power acting on the valves, thus moving the whole linkage, and thus our Johnson bar, attached to the linkage will also be a part of it. But there is another factor, which admits the momentum to the Johnson bar: The weight of the linkage. Usually on a walschaerts gear the whole valve rod, pulls the linkage to the Johnson bar downwards by gravity and weight. On certain other gears, like the Stephenson gear the weight increases because having the radius, and two excentric rods hanging on the linkage or reach rod...

back to our unexperienced engineer who want's to adjust the Johnson bar, we remeber, he is going backwards full stroke and wants to adjust the linkage more to center to drive more economic.

By the load of gravity and the power of steam to the piston valves that handle is teared off his hands and within an eyes blink and much faster than the old rusty ratched could prevent, the lever swings over from back to full ahead... We remember? Steam engines ca be switched from full ahead to full back only by moving the linkage or gears, because you move through the center and this will result in a complete change of all steam flow directions and a full cut off of the steam during the motion throught the center point...

For our steam locomotive this is dramatic, for a steam ship this is really nothing uncommon. But here the adhession betwen wheel rim and track surface prevent the wheels from intermediate change of rotation into the opposite direction and the pushing train won't make the things better! The keep the wheels turn still into the given direction, allowing no change without stop betwen... But the steam does not count on this, it goes into full stroke full force against the given direction and if steam can pull a huge freight train, it can play in such cases also chicken with the engine, so our unlucky engineer gets something, we here call "Spaghetti rods"... The steam force is so brute, that two opposite forces act with damaging effects to the rods and bars against each other... the rod bend or break and thus let the engine completely fail... and also will made the repair team to get a very unhappy task to do...

This we have to consider, and this is why on large engines a Johnson Bar won't be in service anymore. Our screw driven reverser will still move by those forces, but you do not have the problem to keep hold of it, and you can easily move it against all forces. Okay, agree: A browns engine or air driven valve gear adjustment is more comfortable, considering weight and mass of the gear of huge american steam locomotives - but a Johnson bar - no way.

Allways keep two-thrid level in gauge and a well set fire, that's how the engineer likes a fireman